@2023 Selcouthstation. Seluruh hak cipta | 18+ | v1.55

Stasiun Tertua di Indonesia: Jejak Sejarah Perkeretaapian Nusantara

Indonesia, dengan sejarah panjangnya yang kaya dan keragaman budaya yang luar biasa, telah menyaksikan banyak perubahan sosial, politik, dan ekonomi sepanjang tahun. Seiring dengan perubahan ini, transportasi juga mengalami perkembangan yang signifikan, terutama transportasi kereta api. Stasiun-stasiun kereta api menjadi saksi bisu dari perjalanan panjang Indonesia menuju modernisasi. Dalam artikel ini, kita akan menjelajahi stasiun-stasiun tertua di Indonesia, mengungkapkan kisah dibalik mereka, serta dampaknya pada perkembangan negara.

Stasiun Gambir - Jakarta

Stasiun Gambir adalah salah satu stasiun kereta api tertua di Indonesia. Terletak di pusat Jakarta, stasiun ini memiliki sejarah panjang yang dimulai sejak zaman kolonial Belanda. Pembangunan stasiun ini dimulai pada tahun 1883, dan pada tahun 1884, Stasiun Gambir resmi dioperasikan.

Pada awalnya, Stasiun Gambir dikenal dengan nama Stasiun Koningsplein, yang mengacu pada nama lama Jalan Medan Merdeka. Pada saat itu, stasiun ini melayani jalur kereta api menuju Bogor, yang saat itu masih dikenal sebagai Buitenzorg.

Stasiun Gambir menjadi saksi sejarah penting, terutama dalam perjuangan Indonesia melawan penjajahan Belanda. Di dalamnya, pernah terjadi pertempuran hebat antara para pejuang kemerdekaan dengan pasukan Belanda. Hari ini, Stasiun Gambir merupakan salah satu stasiun terbesar dan tersibuk di Indonesia, melayani banyak rute kereta api yang menghubungkan Jakarta dengan berbagai daerah di pulau Jawa dan sekitarnya.

Stasiun Tugu - Yogyakarta

Stasiun Tugu adalah salah satu ikon kota Yogyakarta, yang juga merupakan stasiun tertua di wilayah Jawa Tengah. Stasiun ini dibangun pada tahun 1887 oleh pemerintah Hindia Belanda dan pada awalnya dikenal sebagai Stasiun Spoorweghalte Jojga.

Stasiun Tugu memiliki arsitektur yang khas, dengan atap joglo tradisional Jawa yang indah. Arsitektur ini mencerminkan budaya dan tradisi Yogyakarta, serta memberikan daya tarik tersendiri bagi wisatawan yang datang ke kota ini.

Selama masa penjajahan Belanda, Stasiun Tugu menjadi salah satu pusat pergerakan nasional. Banyak pemimpin kemerdekaan Indonesia, seperti Soekarno dan Hatta, pernah mengunjungi stasiun ini dalam perjalanan mereka menuju Yogyakarta yang saat itu menjadi ibu kota pemerintahan Republik Indonesia yang baru lahir. Stasiun ini pun menjadi tempat bersejarah dalam proklamasi kemerdekaan Indonesia pada tanggal 17 Agustus 1945.

Hari ini, Stasiun Tugu tetap menjadi stasiun kereta api yang penting, melayani perjalanan kereta api dari dan menuju Yogyakarta, salah satu tujuan wisata terpopuler di Indonesia.

Stasiun Poncol - Semarang

Stasiun Poncol, yang terletak di Semarang, Jawa Tengah, adalah salah satu stasiun kereta api tertua di Indonesia. Stasiun ini awalnya dibangun pada tahun 1867 dan dinamakan Stasiun Tawang. Kemudian, pada tahun 1927, stasiun ini berganti nama menjadi Stasiun Poncol.

Stasiun Poncol merupakan salah satu contoh arsitektur kolonial Belanda yang indah. Bangunan stasiun ini memiliki ciri khas dengan atap bangunan yang tinggi dan pintu masuk yang megah. Stasiun ini berlokasi strategis di pusat kota Semarang, dan menjadi akses utama untuk perjalanan kereta api menuju kota ini.

Selama Perang Dunia II, Stasiun Poncol menjadi saksi bisu dari berbagai peristiwa penting. Ketika Jepang menduduki Indonesia, stasiun ini digunakan sebagai markas militer Jepang. Kemudian, stasiun ini menjadi pusat pergerakan perlawanan rakyat Indonesia.

Seiring berjalannya waktu, Stasiun Poncol tetap menjadi stasiun penting yang menghubungkan Semarang dengan berbagai kota di Jawa Tengah dan sekitarnya.

Stasiun Bandung - Jawa Barat

Stasiun Bandung, yang terletak di Jawa Barat, adalah salah satu stasiun kereta api tertua di Indonesia. Stasiun ini dibangun pada tahun 1884 dan diresmikan pada tahun 1886. Saat itu, stasiun ini dikenal dengan nama Stasiun Bandoeng, sesuai dengan ejaan Belanda pada masa itu.

Stasiun Bandung memiliki arsitektur yang megah dan mencerminkan gaya arsitektur kolonial Belanda. Salah satu ciri khasnya adalah atap bangunan yang tinggi dengan sentuhan seni deco yang elegan. Stasiun ini juga dikelilingi oleh taman yang indah, sehingga menciptakan lingkungan yang nyaman bagi para penumpang.

Pada masa penjajahan Belanda, Stasiun Bandung menjadi stasiun penting dalam sistem transportasi kereta api di Jawa Barat. Kota Bandung, yang saat itu merupakan pusat pemerintahan Hindia Belanda, menjadi destinasi yang sering dikunjungi oleh pejabat kolonial dan para wisatawan.

Setelah kemerdekaan Indonesia, Stasiun Bandung tetap beroperasi dan terus mengalami perkembangan. Stasiun ini menjadi pintu gerbang bagi wisatawan yang ingin menjelajahi kota Bandung dan sekitarnya. Dengan berbagai rute kereta api yang tersedia, Stasiun Bandung tetap menjadi stasiun yang sibuk dan penting dalam sistem transportasi Indonesia.

Stasiun Surabaya Pasar Turi - Jawa Timur

Stasiun Surabaya Pasar Turi, yang terletak di Surabaya, Jawa Timur, adalah salah satu stasiun kereta api tertua di Indonesia. Stasiun ini dibangun pada tahun 1903 oleh pemerintah kolonial Belanda dan diresmikan pada tahun 1910.

Stasiun Pasar Turi memiliki arsitektur yang indah dengan sentuhan seni deco. Atap bangunan yang tinggi dan ornamen-ornamen yang menghiasi bangunan ini menciptakan suasana yang unik. Stasiun ini juga memiliki jam tua yang menjadi salah satu ikon stasiun ini.

Selama masa penjajahan Belanda, Stasiun Pasar Turi menjadi pusat pergerakan dan transportasi di Jawa Timur. Stasiun ini melayani perjalanan kereta api dari dan menuju Surabaya, kota pelabuhan terbesar di Indonesia pada saat itu.

Pada masa perang kemerdekaan Indonesia, Stasiun Pasar Turi menjadi saksi dari berbagai peristiwa penting. Ketika pasukan Belanda mencoba merebut kembali wilayah Indonesia, stasiun ini menjadi saksi pertempuran sengit. Stasiun ini juga menjadi tempat penting dalam sejarah perjalanan perjuangan Indonesia menuju kemerdekaan.

Hari ini, Stasiun Pasar Turi tetap menjadi salah satu stasiun kereta api tersibuk di Indonesia, melayani perjalanan kereta api dari dan menuju Surabaya dan sekitarnya.

Stasiun Tanjung Priok - Jakarta

Stasiun Tanjung Priok adalah stasiun kereta api yang terletak di pelabuhan Tanjung Priok, Jakarta Utara. Stasiun ini dibangun pada tahun 1883 oleh pemerintah kolonial Belanda dan diresmikan pada tahun 1886.

Stasiun Tanjung Priok memiliki peran penting dalam transportasi kereta api dan pelayanan pelabuhan di Indonesia. Stasiun ini menjadi titik awal dan akhir bagi banyak perjalanan kereta api yang menghubungkan Jakarta dengan berbagai daerah di Indonesia. Selain itu, stasiun ini juga memiliki jalur khusus yang menghubungkan pelabuhan Tanjung Priok dengan jalur kereta api, sehingga memudahkan pengiriman barang dan logistik.

Stasiun Tanjung Priok juga menjadi saksi dari berbagai peristiwa penting dalam sejarah Indonesia. Selama perang kemerdekaan, stasiun ini menjadi pusat logistik dan transportasi penting bagi pasukan kemerdekaan Indonesia. Sejumlah pertempuran dan aksi sabotase terjadi di sekitar stasiun ini selama periode tersebut.

Hari ini, Stasiun Tanjung Priok tetap beroperasi sebagai salah satu stasiun kereta api penting di Indonesia, melayani perjalanan kereta api dari dan menuju Jakarta serta fungsi logistik di pelabuhan Tanjung Priok.

Stasiun Cirebon - Jawa Barat

Stasiun Cirebon, yang terletak di Cirebon, Jawa Barat, adalah salah satu stasiun kereta api tertua di Indonesia. Stasiun ini dibangun pada tahun 1912 dan diresmikan pada tahun 1915.

Stasiun Cirebon memiliki arsitektur yang mencerminkan gaya kolonial Belanda dengan sentuhan seni deco yang indah. Bangunan stasiun ini memiliki atap tinggi yang khas dan pintu masuk yang megah.

Pada masa penjajahan Belanda, Cirebon menjadi pusat perdagangan dan transportasi yang penting di Jawa Barat. Stasiun Cirebon menjadi pusat pergerakan orang dan barang di kota ini. Pada saat itu, kereta api menjadi sarana transportasi yang vital dalam memperlancar perdagangan dan mobilitas penduduk.

Selama perang kemerdekaan Indonesia, Cirebon juga menjadi saksi dari berbagai peristiwa penting. Kota ini terlibat dalam berbagai pertempuran dan aksi sabotase yang terkait dengan perjuangan kemerdekaan.

Hari ini, Stasiun Cirebon tetap beroperasi dan melayani perjalanan kereta api dari dan menuju Cirebon, serta menjadi pintu gerbang menuju Jawa Barat dan sekitarnya.

Stasiun Solo Balapan - Jawa Tengah

Stasiun Solo Balapan, yang terletak di Surakarta, Jawa Tengah, adalah salah satu stasiun kereta api tertua di Indonesia. Stasiun ini dibangun pada tahun 1873 dan diresmikan pada tahun 1875.

Stasiun Solo Balapan memiliki arsitektur yang indah dengan atap tinggi dan pintu masuk yang megah. Stasiun ini adalah salah satu ikon Surakarta, kota dengan sejarah dan budaya yang kaya.

Pada masa penjajahan Belanda, Solo merupakan salah satu pusat perdagangan dan kebudayaan yang penting di Jawa Tengah. Stasiun Solo Balapan menjadi pusat pergerakan orang dan barang di kota ini. Selain itu, kereta api juga menjadi sarana transportasi yang memudahkan mobilitas penduduk dan perdagangan.

Selama perang kemerdekaan Indonesia, Solo juga menjadi pusat pergerakan nasional. Banyak pemimpin kemerdekaan Indonesia, seperti Soekarno dan Hatta, pernah mengunjungi kota ini dan menggunakan Stasiun Solo Balapan dalam perjalanan mereka.

Hari ini, Stasiun Solo Balapan tetap menjadi salah satu stasiun kereta api yang penting di Indonesia, melayani perjalanan kereta api dari dan menuju Surakarta serta sekitarnya.

Stasiun Malang - Jawa Timur

Stasiun Malang, yang terletak di Malang, Jawa Timur, adalah salah satu stasiun kereta api tertua di Indonesia. Stasiun ini dibangun pada tahun 1881 dan diresmikan pada tahun 1884.

Stasiun Malang memiliki arsitektur yang mencerminkan gaya kolonial Belanda dengan sentuhan seni deco yang indah. Bangunan stasiun ini memiliki atap tinggi dan pintu masuk yang megah. Selama masa penjajahan Belanda, Stasiun Malang menjadi pusat pergerakan orang dan barang di kota ini.

Kota Malang sendiri memiliki sejarah yang panjang, dan stasiun ini menjadi saksi dari berbagai peristiwa penting dalam perkembangan kota ini. Selama masa penjajahan Belanda dan setelah kemerdekaan Indonesia, stasiun ini tetap beroperasi sebagai salah satu sarana transportasi utama di Malang.

Hari ini, Stasiun Malang masih menjadi salah satu stasiun kereta api penting di Indonesia, melayani perjalanan kereta api dari dan menuju Malang serta daerah-daerah sekitarnya.

Stasiun Medan - Sumatera Utara

Stasiun Medan, yang terletak di Medan, Sumatera Utara, adalah salah satu stasiun kereta api tertua di Indonesia. Stasiun ini dibangun pada tahun 1886 oleh pemerintah kolonial Belanda.

Stasiun Medan memiliki arsitektur yang indah dengan atap tinggi dan pintu masuk yang megah. Pada masa penjajahan Belanda, stasiun ini menjadi pusat pergerakan orang dan barang di kota ini. Medan sendiri adalah salah satu kota penting di Sumatera Utara, dan stasiun ini memainkan peran kunci dalam perkembangan ekonomi dan transportasi kota ini.

Selama masa penjajahan Belanda, stasiun ini menjadi saksi dari berbagai peristiwa penting dalam sejarah Indonesia. Setelah kemerdekaan, stasiun ini tetap beroperasi dan melayani perjalanan kereta api dari dan menuju Medan serta daerah-daerah sekitarnya.

Stasiun-stasiun kereta api tertua di Indonesia bukan hanya merupakan bangunan bersejarah, tetapi juga saksi hidup dari perjalanan panjang negara ini menuju kemerdekaan dan modernisasi. Meskipun telah berusia puluhan hingga ratusan tahun, stasiun-stasiun ini masih berfungsi sebagai pusat transportasi yang penting bagi masyarakat Indonesia. Dalam sejarah dan arsitektur mereka, kita dapat melihat cerminan perjalanan Indonesia yang luar biasa, dari zaman penjajahan hingga masa kemerdekaan dan perkembangan ekonomi yang terus berlanjut.

Latest Posts

Deposit pulsa telah menjadi salah satu metode pembayaran yang populer di situs slot online karena kemudahan, kecepatan, dan keamanannya. Bagi mereka yang belum terbiasa dengan proses ini, berikut adalah panduan langkah demi langkah tentang cara melakukan deposit pulsa di situs slot online. 1. Pilih Situs Slot Online yang Menerima Deposit Pulsa Langkah pertama adalah memilih situs slot online yang menerima deposit pulsa sebagai metode pembayaran. Pastikan untuk memilih situs yang tepercaya, aman, dan memiliki reputasi yang baik di antara para pemain. 2. Daftar dan Verifikasi Akun Anda Setelah memilih situs, Anda perlu mendaftar untuk membuat akun. Isi formulir pendaftaran dengan...

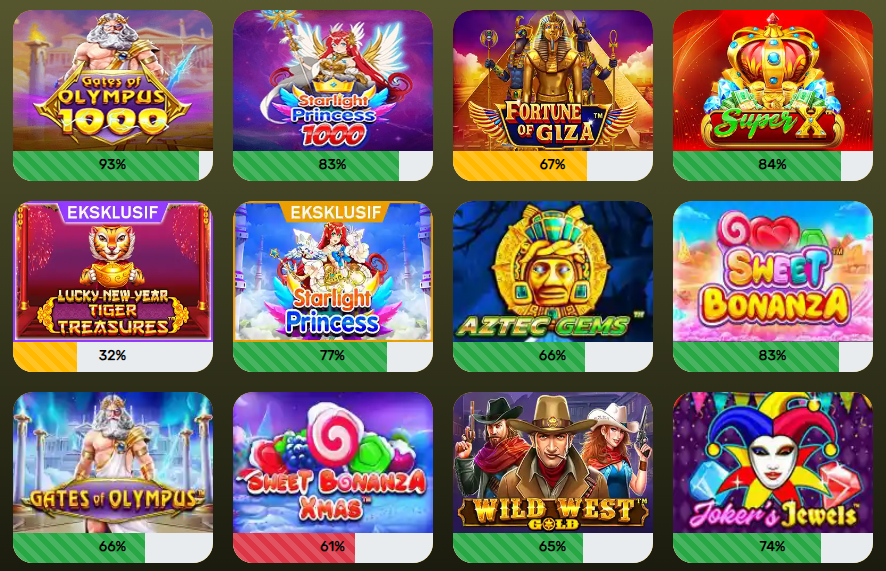

RTP (Return to Player) adalah istilah yang sering digunakan dalam industri perjudian, terutama dalam konteks permainan slot online. Ini mengacu pada persentase rata-rata dari total taruhan yang dikembalikan kepada pemain dalam jangka waktu tertentu. Dalam artikel ini, kita akan menjelaskan mengapa layanan RTP slot penting untuk kemudahan bermain slot online dan bagaimana hal ini dapat memengaruhi pengalaman berjudi para pemain. 1. Meningkatkan Peluang Menang Salah satu alasan utama mengapa layanan RTP penting adalah karena itu memengaruhi peluang menang para pemain. Semakin tinggi RTP sebuah slot, semakin besar peluang bagi pemain untuk mendapatkan kembali sebagian dari taruhan mereka dalam jangka waktu...

Ada banyak pilihan situs gacor slot online terkenal di dunia. Masing-masing situs slot online gacor ini tawarkan permainan dengan kualitas tertinggi. Tentu saja ini bikin para pemain lebih leluasa untuk menentukan pilihan. Terutama slot online terbaik dan gacor yang benar-benar sesuai selera.Saat membahas tentang slot online berbasis video game. Tentu akan jadi lebih sulit untuk menentukan situs mana yang benar-benar terbaik atau gacor. Karena memang ada lebih dari selusin penyedia permainan yang mengklaim sebagai nomor 1. Akan tetapi, ada beberapa situs slot online yang benar-benar banyak direkomendasikan para pro-player atau pemain-pemain berpengalaman. DAFTAR SITUS GACOR SLOT TERBAIK DUNIA Langsung saja,...